Gerhard Richter: Question Everything

By Nancy Nesvet

Gerhard Richter, presently the world’s highest selling living contemporary artist, was born in 1932 Dresden, Germany, growing up between the onset of Hitler’s rule in 1933, a youth spent during the war years, and the rule of communism in the German Democratic Republic. His boyhood was marked by joining Hitler Youth, playing war games with friends wielding toy rifles, and knowing his Uncle Rudy’s Nazi affiliation, serving in the Luftwaffe.

Gerhard Richter, “Val Fex”, Sils, Engadin.

Yet that play with toy rifles was a boyhood game; his uncle seemed miles away from his boyhood world, as he depicted in his later painting, Uncle Rudy. The world detailed in newspapers of those days had little connection with the reality of Richter’s world. Throughout his later arts practice, he would question the veracity of the newspaper, magazine, published photographs and their relation to his connection to that photographed world.

His studies in his five-year course at the Dresden Academy of Art, in a city strewn with the rubble of the war’s bombs, were in the classical figurative tradition. He drew from plaster casts of classical sculpture and nude models. He studied art history, Russian, politics and economics (which he didn’t like). The goal of the program was to produce painters in the socialist realist tradition. Students were not allowed to borrow books concerned with art beyond impressionism because they painted bourgeois decadence. The exception was books about Picasso and Renato Guttoso due to their support of communism. As his studies progressed, Richter joined the mural painting department studying under Heinz Lomar, a tutor who supported his travel to the west.

Reference material for his paintings, outside the mural practice, was hard to come by but his aunt in the west sent him copies of the photographic magazine, “Magnum”, and he kept in touch with art in the west, supported by his tutor to travel to Berlin to see film, museum shows and plays. He took part in an uprising against the Soviet authorities at Postplatz in Dresden on June 17, 1953, but was still rewarded with a studio, teaching and commissions painting muscular men, joyous women and children, leaving him feeling restricted in his subject matter.

He was shown reportage photos at the Academy of concentration camp survivors, later included in his Album, which he refused to paint at the time because “he couldn’t figure out how” (from text at museum installation of Atlas at Whitechapel Gallery, London, opening January 2007)) although he did finally paint Birkenau in 2014, covering it, in his words “with shame or pity or piety”.

In 1959, he went to Kassel for Documenta II. Seeing work by Jackson Pollack, Jan Fautrier and Lucio Fontano led to Richter’s recognition of the creative restrictions prohibiting use of abstraction as a painterly method, changing his entire outlook.

Consequently, on his way home from a trip to Moscow and Leningrad, he stayed on the train until Berlin, where he stored his luggage, returning to Dresden for his wife, Eva. Then, at 29 years old, two months before the Berlin wall was built in 1961, he left the GDR for Dusseldorf where he would study painting at the Dusseldorf Arts Academy.

The next year, he produced his 1962 painting, labeled Painting number 1, the landscape oriented Tisch (Table) portraying a readymade, the image taken from an advertisement in the Italian magazine DOMUS, for Italian furniture design firm, Gardella. Referencing Richter’s labeling as a Pop artist, it also references a “tabula”, becoming the first painting to fill his tabula rasa in the west. As Dieter Schwarz and Nicholas Serota point out in the catalogue to the exhibition at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris in October, 2025, “Everything he had done before was canceled, wiped out, not to be regarded as part of his history.”

Richter painted Tisch in grisaille, then, with newspaper scraps adhered to the canvas, blotted up excess paint, later wiping the surface with paint thinner, literally erasing part of the image. Richter has undone the realistic photographic image, destroying the reality of the photograph, denying the “real” photographic image.

Gerhard Richter, Tisch (Table), 1962.

Richter proceeded to depict images of technological forms, Gothic Chandelier, Bomber [Bombardiers] 1963, Schwarzler, 1964, another plane produced with revered Russian technology. In 1964, Richer paints Kuh, depicting a cow, in German, Kuh labeling the cow image, as in a children’s book. Children learn to identify images with words, spoken and written as Richter has supplied here. We know it is a cow because the word labels it. Yet, the entire image is covered with a large swath of paint, erasing parts of the image as a child might try to erase.

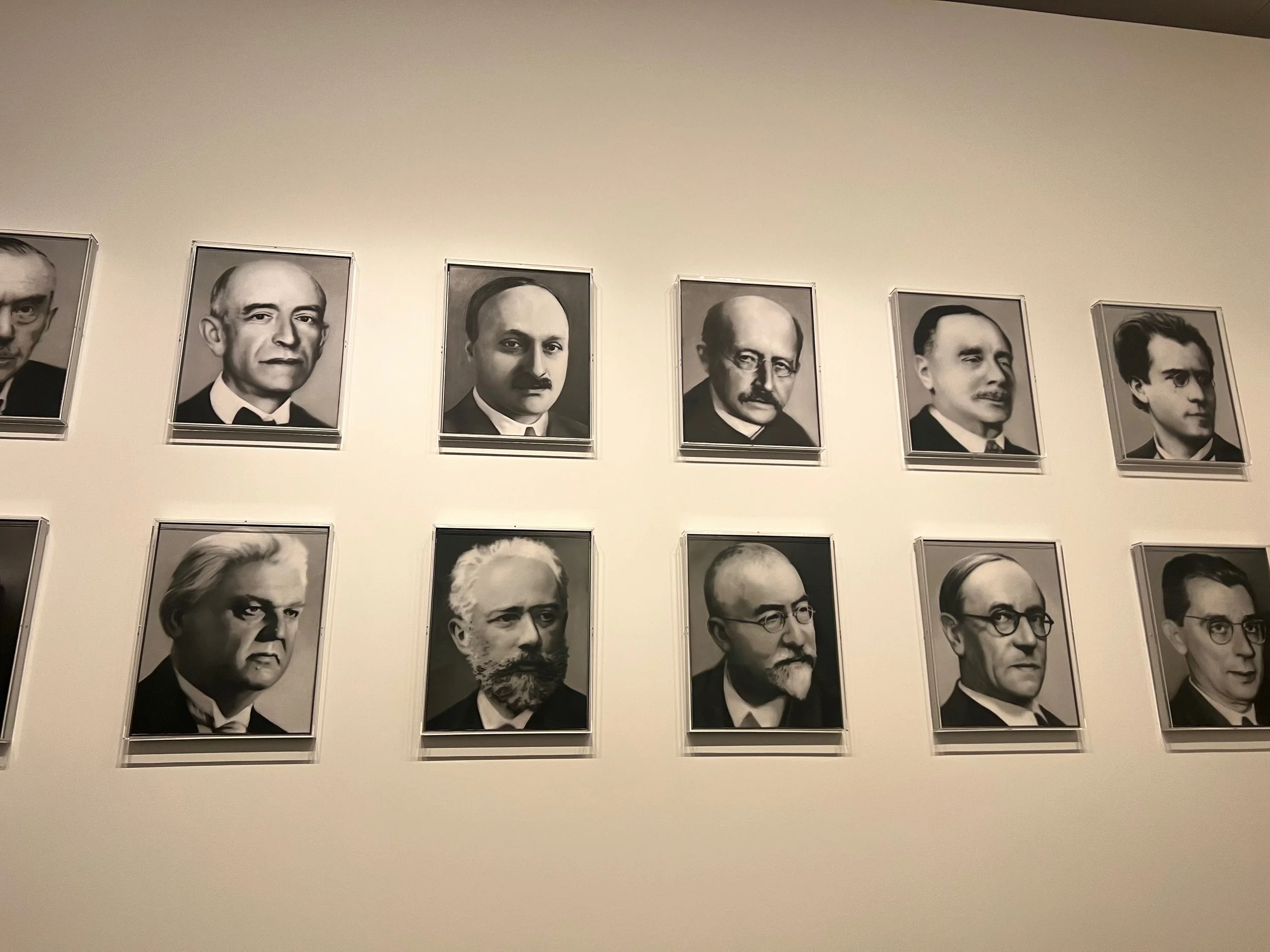

Much later, in the paintings of 48 German twentieth century intellectuals and writers, exhibited at the German pavilion at the 1972 Venice Biennale, Richter did not label the portraits with names of those depicted. They all are white men, outfitted in similar white shirts, jackets and ties, a pantheon of eminent Germans. The pavilion’s neoclassical structure echoes a German past’s concern with neoclassical art. The portraits are sourced from pictures in the encyclopedia, but here Richter has painted them clearly, in grisaille, without any erasures, or lack of focus in the sourced photographs. Illustrating acceptance of eminent Germans in the encyclopedia, does Richter really feign that acceptance, questioning who is in the pantheon and thus, the acceptance by German contemporaries of them and the politics, science and philosophies they accepted and furthered?

At the exhibit at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, all these men surround us, looking down on us from their placement high on the walls. They are all one and the same, in eminence, in nationality, in thinking, part of the same community, so need no identification.

Gerhard Richter, 48 Portraits, 1961-1962, for German Pavilion, Venice Biennale.

All the realistic images in Richter’s oeuvre are painted from reproductions, photographs from the viewpoint of another. In painting them, Richter interprets them, does not add his own emotions, but rather blots out or erases or creates a lack of focus, like the image on a a black and white television or photographic image. He erases emotion from both the photograph and the paintings, making clear his lack of emotional involvement with the image depicted, because that image depicts not his world, nor does he have any involvement in the world it depicts. This is a compendium of historic figures, and they are all from reproductions, never firsthand involvement with the depicted. Richter did not have any firsthand involvement and here, in so many ways, he makes it clear.

Richter’s interpretation of Titian’s Annunciation (Annunciation after Titian (1973) circles back to his labeling of the table, Tisch in his Painting 1.By painting the word Table on the canvas, he identifies, names the image. Here, he depicts, in a series increasingly abstract and out of focus, the announcement, the words of the angel Gabriel directed by God, that Mary will bear a child, the son of God. When Mary finds this unbelievable, the angel repeats the words, to which Mary responds, “Let it be done according to your word”. (translated). The word makes the act promised real. The word becomes flesh, because God has said it will be done. It is this attention and perceived veracity of the word, of newspapers and magazines’ images depicted therein, and in this case, the biblical words, that Richter is concerned with. He is insistent, throughout his career on proving that the image or the words cannot be relied on as truth, certainly not his truth. As he continues to change or erase or schmuge the image, Richter further proves its unreliability. He does not deliver the truth but questions that presented as fact and truth by the media. Richter sourced the image for the Annunciation after Titian painting from a postcard. That common postcard, commercially produced, a cheap and poor reproduction bought by the masses corroborates his contention, expressed in his paintings, of the unreliability of the media, and of reproductions for the masses of fine art, even of biblical themes, proving that quattrocento paintings and later photographs cannot be relied on as expressions of truth. Emerging from his early career in painting propaganda art for the GDR, he rejects the veracity of religious propaganda and of biblical stories themselves, condemning institutions wherever they may be.

We can see the progressive abstraction of Richter’s paintings after the Annunciation after Titian in the exhibit here, as he questions the subjectivity and gullibility of the artist influencing the painting’s depiction on the way to the arbitrariness of the image. We see, in the exhibited paintings at this show, the gesture put onto the canvas arbitrarily and then the attempt to study it, delving into the composition, the depiction, blowing up its proportions for the next iteration on the canvas.

Richters further seems to attempt to organize, as the colors in 1973’s Farben (1024 Colors) and 1974’s 1024 Farben, (1024 Colors). But these paintings are something other than an attempt to organize. There is no apparent organization, no color leads to another, none leads to its secondary or tertiary color. As no one has of yet, as far as I know, counted the colors, and some are repeated so do not count twice or more times, there is confusion as to how many colors are depicted. Is Richter questioning the art establishment? Farben is a firm producing colors for artists. Richter is questioning and then destroying any organization that the art establishment seems to provide, and he will continue throughout his career to destroy composition, content, form, color as we know it and as practiced for centuries and decades before he redefines it, in art as in society.

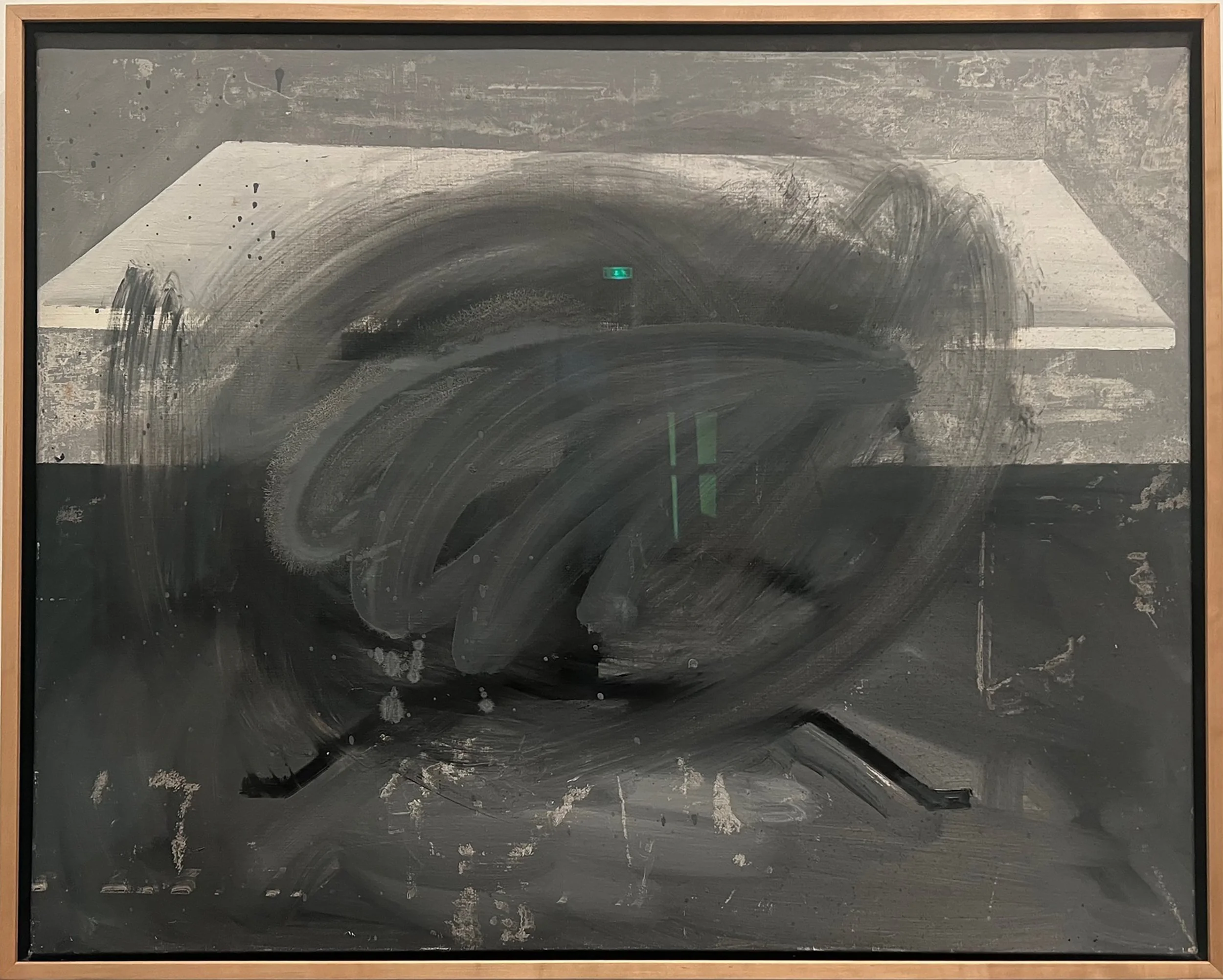

Richter is, at the same time as producing 1024 Farben, producing canvases covered with gray, Grau (Gray), (361-1), (1974), Grau (Gray) 334-3), 1972, 1964’s Grau (Gray) 363-3, (exhibited at DIA Beacon, 2003, and at Deutsche Guggenheim, 2002, 6 panels hung from walls on supports) consisting of different surface markings in a field of the same gray hue. Is he questioning the similarity of the gray paintings to each other, questioning the very definition of the color gray and in 1024 Farben, the plethora and number of Farben colors on the canvas? Are we to take his word, literally, for the gray on the surface, and the number of colors? Here, Richter continues his argument that we believe what we see printed or represented in a photograph, that what we are told or shown, is truth, but that we should not. Is the surface Gray because he labels it such in the painting’s title? Can we take that as truth, or perhaps the graying of truth?

Richter continues the tradition of ordered depiction of colors and grays in the cityscapes. Their grays recall the dour cityscapes of the GDR, consisting of plain, boxes reminiscent of Bauhaus structures, real and imagined. Here again we see Richter posing GDR architecture, challenging it with the knowledge that style has its origins in Bauhaus, condemned by the Third Reich, which preferred German Romantic painting, but which prevailed in the GDR, a land of Communists, condemned by the Nazis. Similarly, he renders the paintings, Jerusalem and Chicago unrecognizable, part of the world that remains after the war, but was built well before the war, perhaps like the Dresden that was destroyed. He has destroyed the links of place to time and hopes to continue to destroy any association of himself with places and times that he chooses to bury in the gray matter of universal devastation. He does the same with his painting of his son, Theo and with his painting of his first wife, Eva descending the staircase, rendering them almost ghostlike, removing them from his world, removing context with himself. Like the photograph, the minute he paints them, he relegates their image to the past, a past that Richter no longer has any association with, if he ever did.

The 18 of Oktober 1977 paintings eliminate political context. The mournful mood of the incarcerated members of the Baader-Meinhoff gang is accentuated by the cell environment, but Richter erases their justification, the political ideology, for committing their crimes. In the Die Stern photographs which portrayed the Baader Meinhoff gang in their cells, the bookshelves were filled with Marxist diatribes. Here Richter removes the titles, the context, the content, the meaning, to let the viewer mourn or condemn. He begs the viewer to interpret those portrayed for good or bad, Marxist or merely revolutionary, but removes the labels begging viewers to see them as people condemned, and some of them do not know the crime. He removes the titles, as words, labels, interpretable, can get their readers in trouble, as happened, as Richter knows during the holocaust, the third Reich, the communist era in the GDR, spoken by governments and especially, the media. And so, he turns to conceptual and abstract art, removing content.

In perhaps his most important work, Eight gray (not shown in the exhibition at Fondation Louis Vuitton) was shown at Pace Gallery in New York in 2002 following 1967’s Glasscheiben, four panes of gray glass on pivots changed viewers’ view of the space as they pivoted, shifting the image and replacing one image with another.

Gerhard Richter, Glasscheiben, 1967.

Recreated for the Guggenheim museum (NY) and then as a site-specific work at Dia Beacon, all these works can be imagined when Richter created them as performance. Richter stood facing the work, seeing. Himself, but then turns toward the viewing crowd, and they see him immersed in their own images reflected in the mirror. He confronts the crowd and stands apart from them, in his own reality. As Dieter Schwarz and Nicolas Serota note in the catalogue to the exhibition in Paris, “4 Glasschreiben [4 Panes of Glass] from 1967…could be considered a metaphor of the infinity of views on reality. You look through the glass and you see a framed picture which does not have a particular meaning. The four panes can be moved into different positions…creating…even more pictures.” Richter’s notes read, “

Glass symbol (to see everything to comprehend nothing”. The catalogue goes on: The clear glass panes …allude to the hope of being free from the terror and tragedy of the past”, and of Richter’s association with that past that he was too young to consciously be part of, confirming it not his past, not his identity. The position and presence of the glass functions as the message, freedom from the terror and tragedy of the past acknowledged by Richter, and yet, his disassociation with that terror and tragedy of Germany’s but not his past, nor his identity.

As Richter continues his journey, methodically destroying what theorists and artists before him have compiled, to find his own artistic identity and purpose and process, he creates the Bach paintings in 1996 and the later Cage paintings in 2006. In the Bach paintings, he references Bach’s systematic, repetitious music, composed during the times of German romanticism. In the Cage paintings, he removes all rules and creates a system whose new rules regenerate with each slightly varied iteration, as Richter, (for the International Pavilion at the Venice Biennale) reacting to one, adds marks; on another, paints all six at the same time. Unlike Robert Ryman’s work, which Richter admired, who removes all context, here, the system is the context. Richter destroys the old, replacing with a new system which repeats for posterity, like history, like Nietzsche’s Eternal Recurrence. He must destroy that old system, and his association to it, and invent that new system which is the expression of his true identity.

Continuing to remove context, Richter goes full abstract, removing even, as much as possible, the painter and the painter’s identity from the canvas. In the mechanical process he invents, sweeping over the canvas with a mechanical arm, laying color upon color, layer upon layer until the bottom layers are completely covered, the identity ascribed to him in his early years, the history of those years during the Third Reich, and then in the GDR, Germany’s history then and in the ensuing years, all covered, not emerging under the uppermost layer, although bits of paint can be detected. [Insert Richter 5 Abstract] All is not, cannot be covered or hidden. Unlike Rothko’s canvases which seem to invite us to penetrate, to delve deeper until we reach darkness, then nothingness, a well and a void, Richter’s get more opaque with each layer, but brighter, strangely with the reds of Richter’s early “The Annunciation by Titian” predominating many of the canvases. It is fitting that these late paintings, with technology interceding, serve as an announcement of the art to come, and that is very much upon us now, not unlike God’s announcement to Mary of what the future holds.

Finally, Richter goes to the Engadin, the place where Nietzsche wrote Thus Spake Zarathustra, inventing the Nazi philosophy that borne the everyman, the era, the history that Richter has spent his life obfuscating, erasing the family stain. He has overpainted, with wide swaths of paint covering large parts of the Engadin mountainscape. The overpainted Engadin photographs are not in the exhibition at Fondation Louis Vuitton. Nicolas Serota, the curator chose not to include them. Could he, like Richter once felt about the concentration camp photographs not bring himself to show them? For whatever reason, these last attempts at erasure, at denial of the familial, the cultural, the historic stain are missing from the exhibition. Richter has succeeded in merging his questioning: He has applied the very real application of paint to the photograph of a very real place but concedes that the view through the camera lens has the shade of technology between his eye and the view, in fact the lens is a pane of glass. The nonrepresentational swaths of paint applied, in fact abstraction are in fact more his reality than that seen by and through the camera lens, as the panes of glass in Eight Gray and Der Schreiben illustrated years ago. He has modulated the photograph, the camera’s lens, and the reproduction with his own painted marks, his own reality. Long after Richter first visited the Engadin in 1989, after the work was shown in 1992 in the exhibition at Nietzsche Haus in 1992 curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and compiled in the small chapbook, Sils, Richter ceases to paint. He goes back to the most elementary artistic progress. He draws and has not stopped drawing. He has erased his past, the Nazi era’s past, his native country’s past in relation to himself and finally freed himself to establish his own identity, not that imposed on him by others nor the media. He has left that place, the Engadin, Sils, where Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra was written, leaving behind the never-ending Eternal Recurrence, establishing and corroborating his identity through his artistic practice, and triumphed at last.

Drawings, as seen in the final section of the exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton requires close work, unlike wide swaths of paint. It is not muscular work, but detailed, requiring not strength, but rather control, the variation of line dependent on the gentle force of hand, Richter’s hand, with no copying nor technology involved other than the pencil held, like a child.