Bone Music Resurrection

By Richard Humann

I first stumbled upon the history of bone music while researching another art project. I had the idea to write and record an audio timeline narrative of an individual’s lifetime, from birth to death, and then press the sound piece onto vinyl. The idea was inspired by the Friedrich Nietzsche concept of Eternal Recurrence, a thought experiment, and philosophical concept suggesting that life repeats itself identically and infinitely. After recording the work, and pressing it onto a vinyl album, I would put the record on a turntable and let it play over and over again continuously, until the diamond needle etched its way entirely through the vinyl. Each lifetime played on the record would be nearly identical, but slightly different, slightly more damaged, fading off like an echo into eternity.

Richard Humann, “Tomorrow I’ll Miss You”, Original music pressed into polycarbonate flexi discs, ink on paper, steel, 7.5 x 7.5 in each, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Leonovich Gallery.

With most of my new art ideas, I spend time researching the history, exploring how I might find a new creative angle, various ways of producing the work and presentation possibilities. I was researching how to press individual vinyl records when a link for bone music popped up on the search engine. I clicked, beginning a deep dive into researching this unique musical phenomenon.

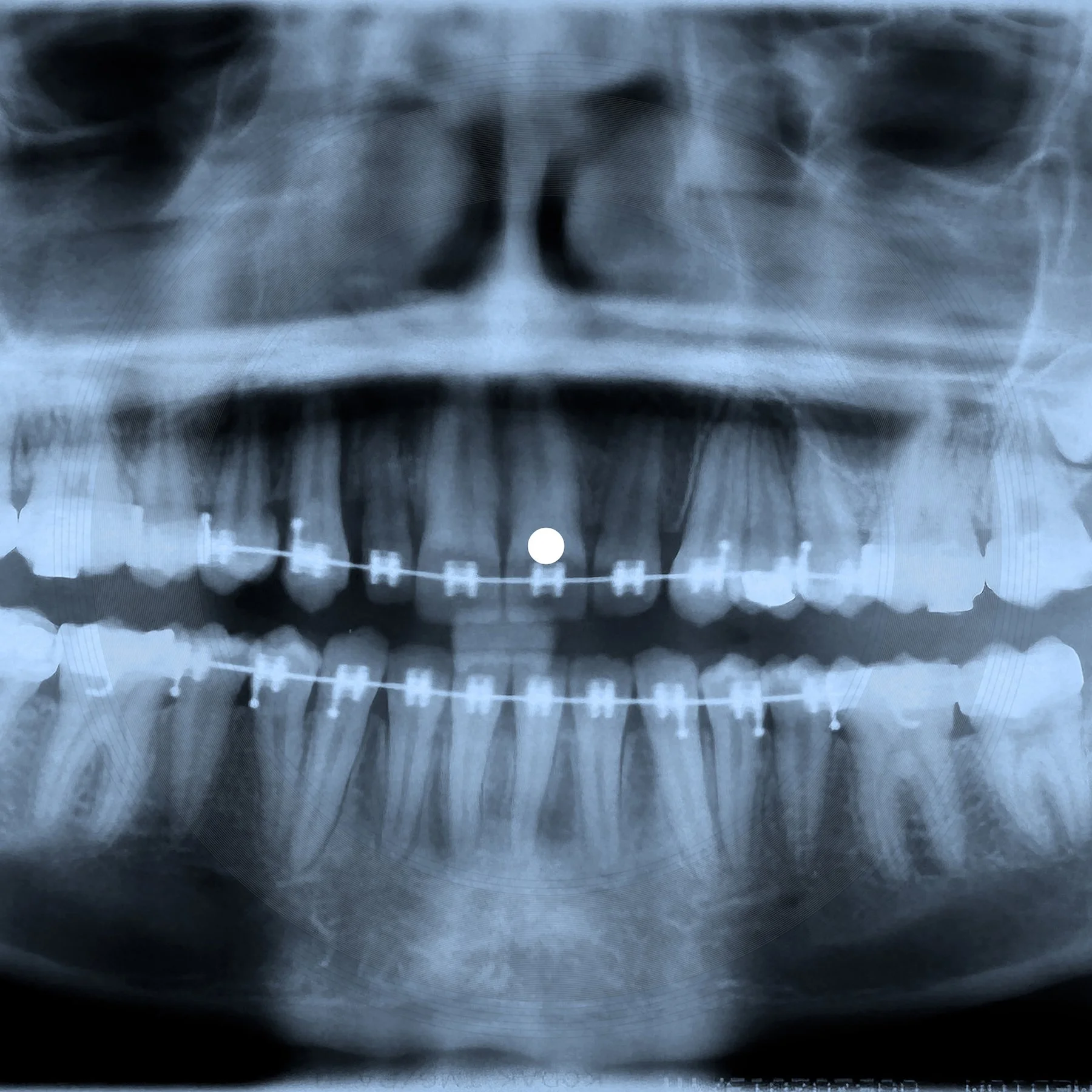

Bone music is known by a few different idioms, including jazz on bones, music on ribs, ribs, and roentgenizdat. The terms refer to illegal, bootleg records that were made behind the Iron Curtain of the Soviet Union throughout the 1950’s and 1960’s fulfilling the desires of western music fans to hear banned music. Western jazz and rock & roll music were pressed onto discarded medical X-ray films that were purchased or picked out of the trash from hospitals and clinics. Once pressed onto the X-rays, the records were smuggled and distributed on the black market. The uniqueness of these artifacts, showing ribs, sternums, vertebrae, femurs, skulls and more of the 206 bones found in the human body, was a creative act of defiance against censorship. These low sound quality, Cold War records, purchased or sold through the underground came with the risk of imprisonment, but show the insistence, at great personal risk, of creating access to and hearing western music and lyrics. Banned artists of the time include Elvis, The Beach Boys, Ella Fitzgerald, Chuck Berry, The Rolling Stones, and of course, The Beatles.

One of my earliest memories as a very young child was my mother sitting me down in front of the television set at two-years-old the night that The Beatles first performed on The Ed Sullivan Show. In truth, I don’t quite know if I actually remember it, or if I had heard the story so many times that it seems like a real memory. She told me, “After tonight, the world will never be the same.” And it wasn’t. Ozzy Osbourne said of that evening, “It was like going to bed in a black and white world and waking up in color.” I wouldn’t read that quote until many years later, but he was right, the world was in color now.

There are so many moments like this throughout history, both distant and recent, where art, music, literature, and the performing arts, have changed the course of the world. I’ve always believed that art has the capability and the power to do just that. It certainly changed me, from a kid growing up in a small town in upstate New York, to who I am today, an artist in New York City—the cultural capital of the world.

Richard Humann, “Tomorrow I’ll Miss You”, Installation view at Leonovich Gallery, New York City, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Leonovich Gallery.

I grew up in a politically charged household. During the late years of the Vietnam War, my mother was vehemently anti-war, a member of the organization Another Mother for Peace, an anti-war protester and a firm believer in the civil rights and equal rights movement. A beautifully gilded plaque was mounted on the wall above the French doors in our living room that read ‘A woman’s place is in the House…and in the Senate.’ My mother wore a POW bracelet on her wrist, and a peace sign around her neck. My father on the other hand, was a conservative Republican, what we would call today, a “Goldwater Republican” who focused on fiscal responsibility and maintaining the status quo at a time of tumultuous upheaval. There were spirited political discussions every night at dinner, that never turned personal between them.

Much like the illicit X-ray bone music that existed underground, as soon as my father left for his day job or night college classes, Abbey Road, Moondance, Sweet Baby James, or the double-vinyl album, Woodstock: Music from the Original Soundtrack would play on the record player. The Country Joe and the Fish song, Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die, or Pete Seeger’s Where Have All the Flowers Gone played constantly in our house, these songs of protest in the era of American turmoil showing me what the power of strong conviction, and art could achieve.

When I was given the opportunity to create the solo exhibition at Leonovich Gallery in New York City that opened this past November, I was fully committed to creating a body of work that used bone music as the central core of the concept. The gallery had offered me the exhibition over a year ago, which gave me that time to develop a multi-level approach. I am not a political artist per se, meaning the major dialogue of my work is not politically motivated, but I could not overlook the parallels between the time period when bone music existed and the times that we live today. Much like Nietzsche’s Eternal Recurrence, there are ever-recurring themes of censorship, repression, and the chiseling away of democracy within the scenario of totalitarian dreams of empire.

I wanted to include a sound element in the exhibition, as well as filling the gallery with individual works that together would make an entire installation. I wanted to honor the uniqueness of bone music pressed onto X-rays but present it in contemporary style. Searching for ways to produce the records, I made sure that the sound would be of the same sonic quality as contemporary music production, but I also needed the final physical product to be archival. I reached out to multiple manufacturers and was directed toward someone within the city who could press the music onto flexi discs. These discs were a thicker material than an actual X-ray and would allow the record to be played many times over, as opposed to an actual pressed X-ray where the average number of plays is only five to eight before total degradation occurs. I chose square flex discs onto which to press the music which gave it a more enigmatic aesthetic appeal.

I purchased the X-rays in bulk from doctor’s offices, veterinary clinics, and dental practices. I then scanned the back-lit X-rays to high resolution files and had them printed on acid-free, archival, translucent paper. They were then face-mounted to the back of the clear flexi disc. Unlike the original bone music X-ray singles, where a lit cigarette was used to burn the spindle hole, mine were pre-cut-out on the flexi disc, but I used a scalpel to trim the face-mounted print. In all, 66 individual, unique pieces were produced.

Richard Humann, “Life Ain’t Funny (When You Wake Up Dead)”, Original music pressed into polycarbonate flexi discs, ink on paper, steel, 7.5 x 7.5 in each, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Leonovich Gallery.

Along with being a full-time artist, I also write lyrics for the band American Nomads. I knew that I wanted to write the lyrics for the songs in the exhibition, so that I could continue to drive the narrative and fold it neatly back into the original concept. I wasn’t sure yet whether I wanted the band to create the music, and if so, what kind of music it would be. I was uncertain regarding the various options (at the conceptual level), considering how the music would associate with the physical objects of the work. My ideas went from putting one individual track on each single so that together they would all create the sound of one song, to having dozens of different bands pick a cover song to give me to burn onto a disc, to trying to gain the performance rights of the original music of the time period that the exhibition fits into, and a multitude of other ideas. Ultimately, I decided to write lyrics to songs that were indicative of the time period. I then wrote lyrics for six songs that I felt would represent a cross-section of that era. They went from more fun and loose to revolutionary and revolt. It was during this process the idea sprang forth of using AI to create the music for the lyrics.

I wouldn’t choose to use AI to create music that was to be released into the world as just music, but it was a natural fit for the concept of this art exhibition that dealt with censorship, politics, black market and, of course, revolution. I began learning an AI music program and realized that the prompts that I needed to create the music were very similar to the explanations that I give the band when turning over my lyrics to them. When I send the band my lyrics, I include an idea of my thought process on the song. I write with a rhythm in my head, and often hear instrumentation, vocal style, and tempo along with that basic rhythm. I have a clear idea of how the lyrics will be converted into the musical application, and I convey that messaging to the songwriters. Often they do not listen to me and choose their own interpretation of the lyrics to apply to the music, so that when I hear the completed song, it is always a surprise, and often much better than I could have imagined. The AI experience was similar in a way, but different because it took my prompts and then gathered references to create the music. I found that writing the prompts was equally as important as the lyrics, because this hybrid of prompt/poetry and prosaic instructions is what advanced the full development of the songs.

Richard Humann, “Dead Horse Bay”, Original music pressed into polycarbonate flexi discs, ink on paper, steel, 7.5 x 7.5 in each, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Leonovich Gallery.

An example of one of the lyrics and prompts for a song in the exhibition is:

DEAD HORSE BAY

[Mood: Uplifting]

[Energy: High]

[Music Style: Early Rock, 1960’s]

[Vocal: Female] [Soprano]

[Vocals: Double Track Lead]

[Vocal Style: Confident]

[Instruments: Electric Guitars, Bass, Drums]

[Verse 1]

She walks along the empty beach

The sands of time have finally reached

The end of the hourglass

Barefoot in the salted sea

The surf now rises to her knees

Like memories of the past

[Pre-Chorus 1]

And she weeps for another day

As a passing ship of hope steers away...

[Chorus]

From Dead Horse Bay

[Verse 2]

The tears fall from her sunken eyes

A broken heart alone she cries

An ocean of regret

A seagull screams into the wind

She turns her head and thinks of him

A love she can’t forget

[Pre-Chorus 2]

And she wishes it were child’s play

That brought her here and led her astray…

[Chorus]

To Dead Horse Bay

[Bridge]

The tide turns quickly through the years

A rise and fall of smiles and tears

Of love both won and lost

The undertow it will enslave

And pull you to a water’s grave

But that is just the cost

[Guitar Solo: Electric Guitar, 1960’s Tone]

[Pre-Chorus 3]

Of a heart that’s on display

And a dream that’s faded slowly away…

[Chorus]

At Dead Horse Bay

[Verse 3]

She inches further from the shore

Hoping this will be the cure

For all the pain she holds

A drowning sorrow rises up

A sober thought, do not give up

There’s more life to behold

[Pre-Chorus 4]

Yes, there’s a new pathway

And on dry land she just walks away…

[Chorus]

From Dead Horse Bay

Styles> Early Rock, 1960’s Rock and Roll

Advanced Options> Surf Sound, Clapping

Vocal Gender> Female

Style Influence> 80%

The full lyrics and AI prompts were printed in large format for all six songs and displayed in the gallery during the exhibition to give a view to the inner workings of the process.

Richard Humann, “Turntable”, Video with sound, Variable dimensions, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Leonovich Gallery.

As for the title, I ultimately decided upon Tomorrow I’ll Miss You, which is a line in The Beatles song, All My Lovin’. It had the multi-faceted and double entendre underpinnings that I simply love in a title. It worked within the context of the body of work, it referenced the music of the time period, the memento mori of the visual content of the X-rays, and the tenuous firewall between mankind and AI. It simultaneously spoke of the past, the present and the future.

When I was first introduced to the history of music pressed onto X-rays and passed around through the channels of the black market, it made me think of so many other times in history where underground art meant more than just pencil marks on paper, brush strokes on canvas, spray paint on a wall, or notes on a recording—these grooves pressed into radiographic film truly represented freedom of thought and freedom of expression, all at the risk of losing that individual and collective freedom from incarceration if caught. It is that pursuit of freedom that has always resonated with me as both an artist, and as an individual. The dialogue that I am provoking in this exhibition are multi-faceted and multi-layered. I’m trying, from the historical reference of bone music and all that it encapsulates in relationship to creativity, freedom, and the oppression of censorship. I’m also drawing upon the concept of revolution. More than just artistic revolution, but actual revolution that alters the paradigm of an existing system, of course referenced in the revolution of the record as it plays.

Richard Humann, “Tomorrow I’ll Miss You”, Installation view at Leonovich Gallery, New York City, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Leonovich Gallery.

The radiographs in the exhibition see into the human body, viewing bones and organs, but do not look into the inner lives, inner desires, and inner emotions of their subjects. X-rays capture bone and tissue; the music and lyrics pressed onto the material that serves as a ground for the X-ray capture our inner lives, our thoughts, emotions and feelings. The electromagnetic radiation waves of an X-ray are less powerful than the sound wave. The electromagnetic radiation wave goes through the body, but the sound wave goes into the soul of human beings. It is through that window that we encounter what cannot be seen, but what can be felt, what can be heard, and what can be experienced.

Tomorrow I’ll Miss You is an exhibition filled with a body of work that acknowledges the historicity of clandestine bone music, and serves as much a warning to the oppressors as it is a promise to the oppressed, that as history repeats itself, art always triumphs.