Process and Invalidation

By Jorge M. Benitez

The means by which we arrive at a conclusion, achieve a goal, or make an object belong to the category of process. A process can be intellectual, emotional, scientific, technical, legal, or biological. A process can also be simple, straightforward, arduous, or tedious. Our understanding of the term is as varied and convoluted as its applications. As with all words and concepts, it also changes over time. It has no fixed meaning, a fact that enhances its suppleness and usefulness while adding layers of confusion. To say, “I am changing my painting process,” is not the same as, “I’m in the process of divorcing my spouse.” Artmaking and executions all use processes. Yet their ends are altogether different except, perhaps, for the unfortunate witness to bad art.

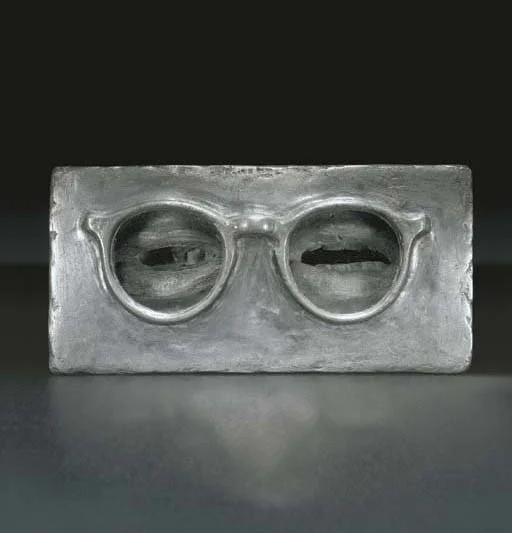

Process grew in importance after 1945 as American universities replaced independent art schools. Art programs were compelled to follow the rigors of science and the scholarly seriousness of the humanities while the studio metamorphosed into a lab devoid of bohemian irreverence. In addition, the very nature of postwar universities combined process with research to produce a quasi-academic discipline replete with its own grammar, syntax, arcane vocabulary, and philosophical ambitions. By the late 1990s, it seemed that language had completely overtaken vision in a manner reminiscent of Jaspers John’s satirical sculpture The Critic Sees, a pair of eyeglasses with open mouths for eyes. The sterile gaze of the visual eunuch had replaced the passionate encounter between art and the audience that could inspire a succès de scandale, or at the very least, a quick exit from an opening. Under the circumstances, it is easy to imagine Michelangelo speaking at a conference in 2025 and stating with the obligatory and conveniently self-exculpatory opening gerund, “Researching the intersection of chisels and religiosity, through a process that requires the incremental removal of material from a block of marble, explores an encounter with the phallocentric identity of a disempowered biblical figure exploited through an asymmetrical power dynamic.” The avant-garde academy had at last achieved the respectability it craved by manufacturing theory-savvy graduates armed with an exegetical-hermeneutical arsenal designed in France and built in America. The mouth had at last replaced the eye of the artist.

Jasper Johns, “The Critiques Sees” (Sculpture), 1961.

As early as 1964, an unlikely source addressed the exegetical-hermeneutical takeover in an essay titled “Against Interpretation.” Against Interpretation and Other Essays was published in 1966. With biting freshness, Susan Sontag wrote, “Interpretation, based on the highly dubious theory that a work of art is composed of items of content, violates art. It makes art into an article for use, for arrangement into a mental scheme of categories.”[1] Content, it seemed, was external to the visual work of art. Interpretation demanded a programmatic imposition on a non-verbal and non-narrative experience whose intent and meaning could never be known fully. Whether this narrow understanding of “content” is right or wrong is not as important as Sontag’s claim that, “It makes art into an article for use, for arrangement into a mental scheme of categories.” The question is, who turned it “into an article of use”? The answer was already clear by 1966. The “article of use” served the critic, the art historian, the dealer, and increasingly the activist for whom art was merely a process by which to achieve a sociopolitical end. The artist could argue that the work of art and its formal workings comprised the content, but the wordmonger held the power of the tongue and the pen along with the bludgeon of pedantry. Vision, that animalistic sense whose value had been in doubt since Plato, could not compete with the word-based “mental scheme of categories.

The “mental scheme of categories” was embedded in a Western legacy that stretched from Plato to Descartes and culminated with a Linnean obsession with categorizations that still plagues Western discourse. From Genesis itself, the West inherited a penchant for separating, naming, and cataloguing that still demands that everything that exists be assigned a label. Furthermore, the United States, the same country that had overtaken the art world after 1945, was dedicated to a level of segregation that exceeded the bounds of racism in ways that still influence what outsiders see as an American inability to think beyond atomized details. The Land of Opportunity was becoming a land of easily bored Mandarins seeking the frisson of the-new and-improved as it progressed steadily away from the capacity to see beyond the immediate. As Americans abandoned long-term goals, patience, and the long view of history, a section of the arts placed process above making, as if the latter were an embarrassing reminder of art’s links to techne and techne’s links to slavery, workers, women, and the hand. Slaves, workers, and women made things. Artists engaged in ideas. In the new aristocracy, thinking was a process above making, and, as in theoretical physics, pure research was the highest form of process. Henceforth, art would be reduced to an intellectual endeavor. Fortunately, most artists never got the message. Whether they work alone or require a team of assistants, artists ranging from Jenny Saville to Takashi Murakami still make art that stimulates the senses and the metaphorical soul.

Jenny Saville, “The Anatomy of Painting” National Portrait Gallery, London.

Regrettably, it is easy to conflate a critique of contemporary aesthetic dysfunction with an old-fashioned advocacy for mimesis, as if the war between representation and non-representation were still relevant. Nonetheless, the critique of conceptual overreach exceeds the limits of outdated modernist battles and addresses an issue with Socratic-Platonic roots, namely, the negation of physicality beginning with the senses. The anti-mimetic, or iconoclastic, argument attacks representation only as a first step toward the invalidation of the physical world. In a salvo against materiality, Socrates said: “The art of representation is therefore a long way from truth, and it is able to reproduce everything because it has little grasp of anything, and that is little of mere phenomenal appearance. For example, a painter can paint a portrait of a shoemaker or carpenter or any other craftsman without understanding any of their crafts; yet, if he is skillful enough, his portrait of a carpenter may, at a distance deceive children or simple people into thinking it is a real carpenter.”[2]

The Socratic assault extended beyond a questioning of vision and into a promotion of idealism that still haunts the West with tragic consequences. By portraying the carpenter, the painter merely added mimetic insult to the filth of physical action. As Alain Besançon explained, “The Form is not extracted or abstracted from the sensible object. Rather, that the object works to reproduce—but without success—the brilliance of the Form. The Form is eternal, and the copy, a collection of sensible qualities, rapidly undone by change.”[3] In short, the artist had blasphemed against the “Form,” the invisibly pure spirit of divine reason. Abstraction itself could not escape the sin because it resulted in a physical product that could suggest the world, if only through analogy and simile. Non-representation was as much an affront to the “Form” as the most philistine still life.

In light of this anti-sensual philosophical legacy, the artist who aspires to something higher than art has no choice but to abandon the making of things in favor of a contemplative union with pure thought. Whatever physical expression results from this communion with Forms must be relegated to a lesser being who still makes things. Thus, the artist divorces process from making until such time as the craftspeople can be eliminated altogether and whatever passes for art can emerge with minimal human interference from the perfect womb of a digital maker. At that point, process becomes an invalidation of art, a negation of life.

The preceding paragraph is not a rejection of digital tools. Instead, it is a warning against the delusion of intellectual superiority through material disengagement. Unlike bodhisattvas who accept the world as it is, Western saviors often reject the world for the sake of unattainable perfection. All-too-often, the process kills millions. Nearly a century before the current idealist rush toward the abyss, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote: “Like form, a concept is produced by overlooking what is individual and real, whereas nature knows neither forms nor concepts and hence no species, but only an ‘X’ which is inaccessible to us and indefinable by us.”[4] Pain, death, joy, and life are all “individual and real expressions” beyond the reach of definitions. They defy the Western chatterbox of endless analysis and interpretation. They exist outside the absurdity of meaning and purpose. They are indifferent to the platonic Logos and reconnect the artist to the earth and the goddess through the tragic fertility at the core of art.

We must return to Sontag. Her claim that art had been reduced to “an article of use” must be understood in a new, far more mercenary context than she could have imagined. “Against Interpretation” ends with a Dionysian plea: “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.”[5] Eros embodies and reifies love, passion, sex, and physicality. The god is an androgynous antidote to the “mental scheme of categories.” He is also a challenge to the puritanism and repression at the core of American intellectualism even when it aspires to “looseness.” It is impossible to know if Sontag understood the depth of her plea or if she was even sincere. How can we fathom the truth of a decade that seamlessly folded irony and mockery into escapism and called it love? If Sontag was indeed sincere, then her plea assumes a tragic dimension beyond the scope of the Swinging Sixties. Today’s reality exceeds the countercultural cynicism of a decade that sowed the seeds of the twenty-first-century debacle. What need is there for art of any kind in the disembodied world of ones and zeros? What need is there for humans, beginning with those who make things, in a society that may render workers irrelevant; a society that may end poverty by exterminating the poor? Those artists who think that their conceptual superiority will save them from a culling of the herd need only look toward Silicon Valley to see their future. Then again, we should not underestimate the power of non-art accompanied by pages of exegetical dreck. Incomprehensibility may grant humanity the power to short-circuit the Terminator.

[1] Susan Sontag, "Against Interpretation," in Against Interpretation and Other Essays (New York: Picador, 1966), 10.

[2] Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lee (Middlesex: Penguin Book Ltd., 1974), 426.

[3] Alain Besançon, The Forbidden Image, An Intellectual History of Iconoclasm (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 26.